INCREDIBLE

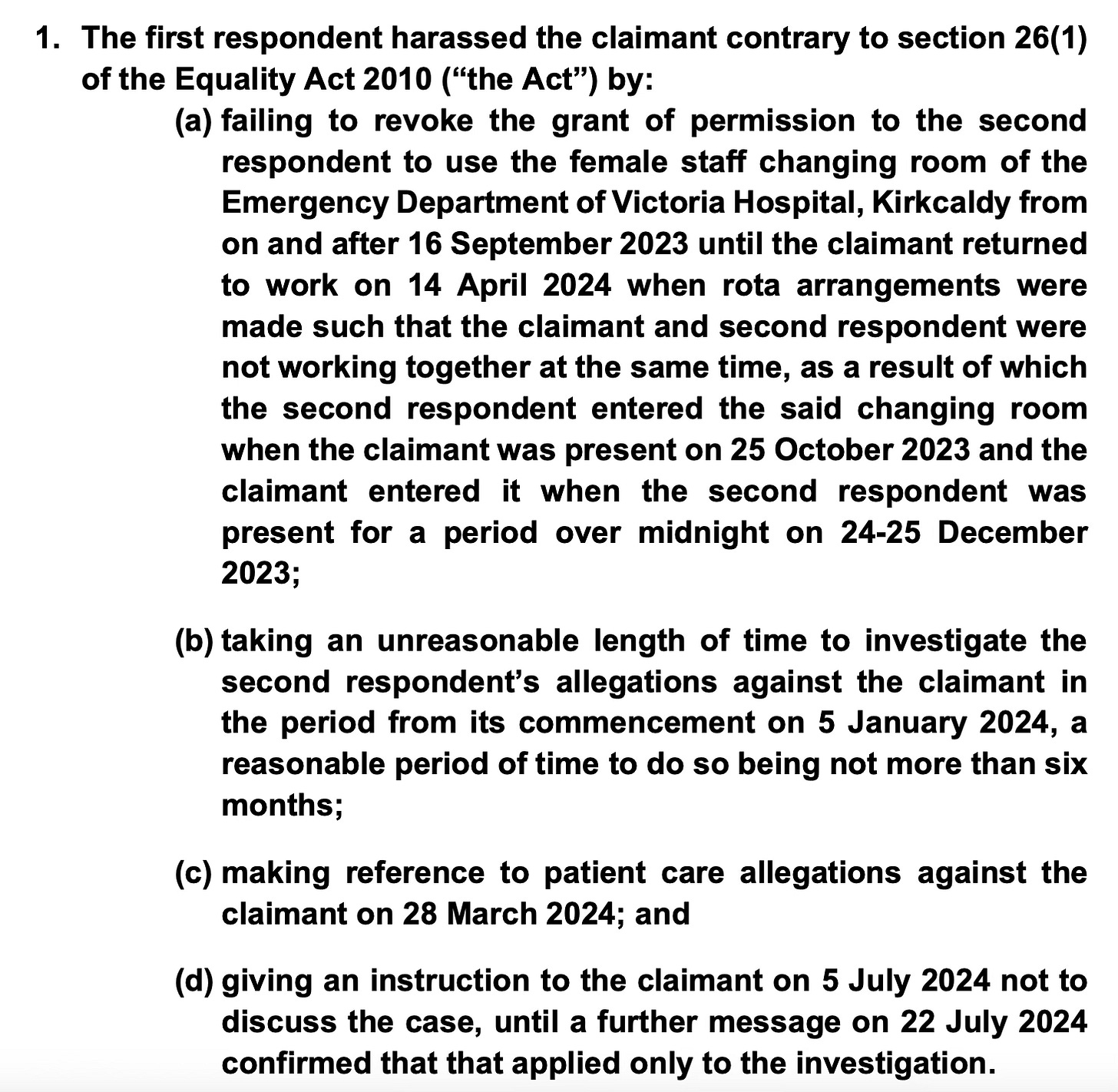

How the scales of justice were tipped in the Sandie Peggie employment tribunal

SOMETHING very odd happened when the Sandie Peggie employment tribunal delivered its judgment - and it wasn’t just the made-up quotes and mangled law.

Call it institutional bias, ideological capture, or just the law doing its job, but what Judge Sandy Kemp’s tribunal delivered was the most one-sided outcome since Butch and Sundance decided to come out shooting.

Every single member of the NHS Fife side was accepted as a credible witness. But Peggie and her team were cut down in a hail of negative conclusions. It seems worth spending a little time with the judgment to understand how this happened.

Peggie, a senior nurse, had been suspended for objecting to what the tribunal ruled was a male doctor, “Beth” Upton (who identifies as a woman) being in a changing room reserved for female staff.

Peggie won her claim of harassment against NHS Fife because, among other failings, they didn’t provide her with a single-sex changing room and because they made such a mess of trying to hang her out to dry for standing up for her rights.

On pretty much every other point the tribunal found against her. At the heart of it all was a simple question: who, out of a middle-class doctor and a working class nurse, was most credible? It was definitely the doctor, the thoroughly middle-class tribunal decided.

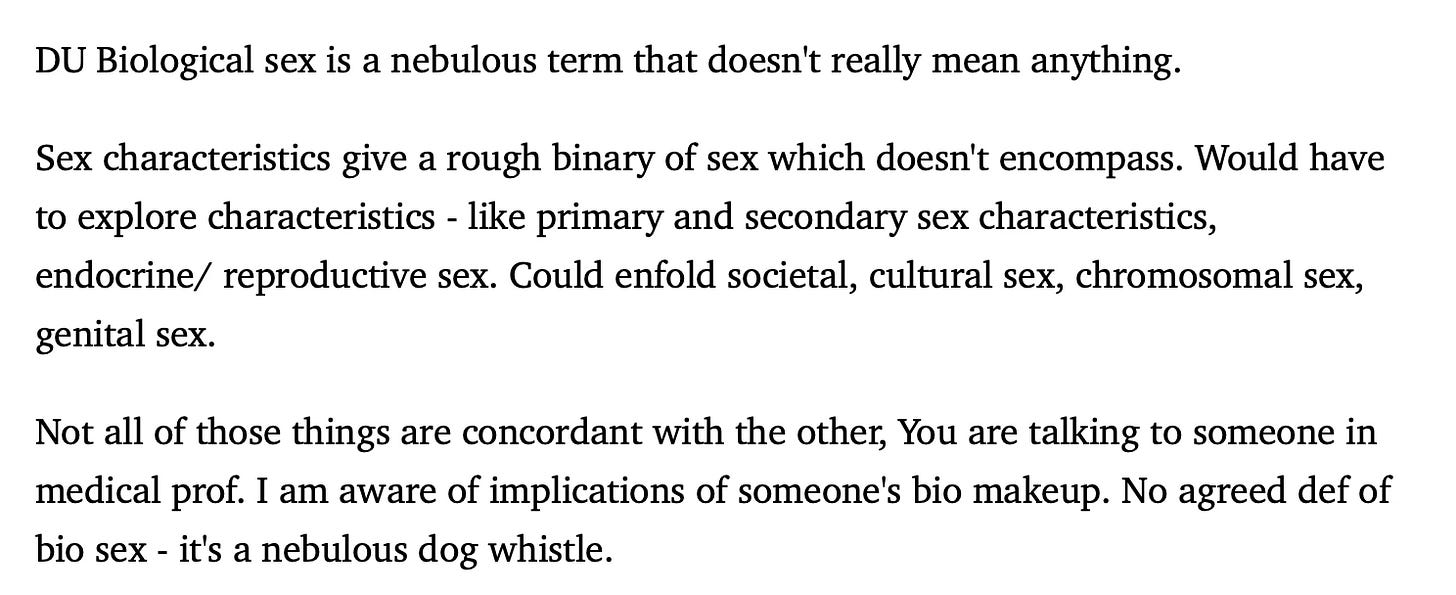

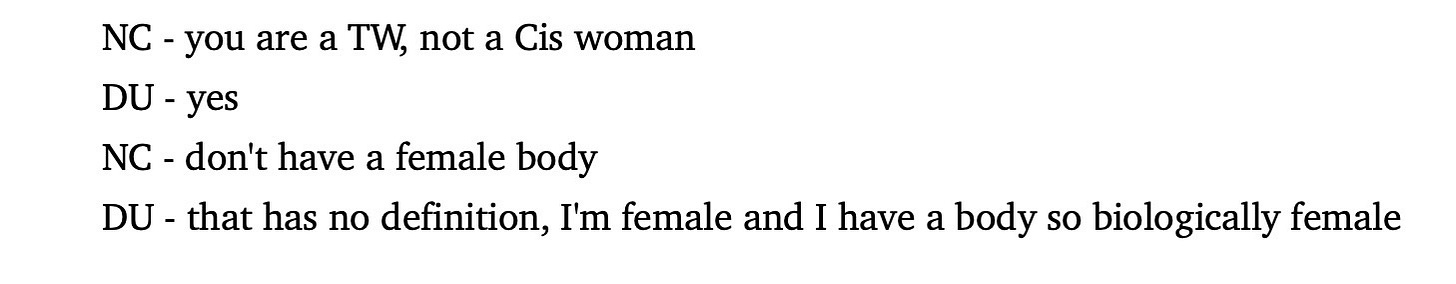

This despite Upton having informed them that he was a biological woman, but that biological sex was a “nebulous dog whistle”. They ruled that he was actually a man, but still they believed him on everything else.

And it wasn’t just Upton they believed. Those the tribunal found to be credible included an equality and diversity officer who didn’t know whether she was a woman or not.

Also credible was a doctor who admitted breaching the confidentiality of an investigation. And another doctor who couldn’t explain why she made up a claim about Peggie.

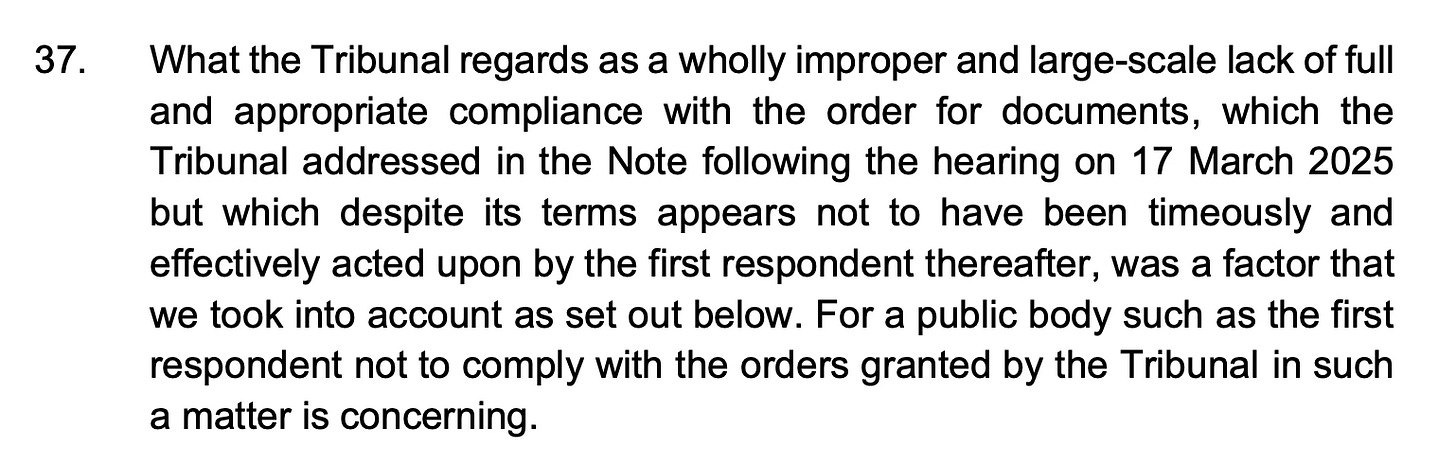

So-called “contemporaneous” notes made by Upton had been changed. NHS Fife tried on a “wholly improper and large scale” to prevent the tribunal seeing evidence. There was a secretive “need to know” group involved in the investigation.

And still, after all that, the tribunal preferred the word of the NHS Fife side to that of a nurse with an unblemished 30 year record.

“not since Butch and Sundance came out shooting has there been a more one-sided outcome”

Wherever there was a difference of opinion about what happened, it was the evidence of her colleagues that was believed. Peggie’s own credibility was called into question and she was branded transphobic.

There are shades about this of the Not The Nine O’Clock police sketch in which Rowan Atkinson questions the over-zealous Constable Savage on why he’s arrested the same man 117 times. “He’s a villain sir,” comes the reply. Peggie, from the outset, was cast as the villain.

Those on her side also faced criticism. Peggie’s lawyer Naomi Cunningham was accused of “misgendering” Upton in a way that in other circumstances, the tribunal said, may have constituted harassment.

Maya Forstater, whose own tribunal this one misquoted, had her evidence dismissed as unreliable and her answers to questions described as not candid. It was Forstater’s appeal against an employment tribunal that established that gender critical beliefs are protected under the Equality Act 2010.

Some background: Peggie had complained about Upton using the female changing rooms at the Victoria Hospital in Fife before matters came to a head and she confronted him on Christmas Eve 2023.

Nurse manager Esther Davidson, who handled complaints, had previously told her she could change in the toilet or a store room. Peggie said she did not want to.

On Christmas Eve she noticed she had heavy menstrual bleeding and went to the female changing room to change. Upton was there. Peggie told him she didn’t think that was appropriate. They argued and he subsequently complained about her behaviour.

So why did the tribunal come out so heavily on the side of NHS Fife? The judgment focused on the confrontation in the changing rooms and three specific elements of Peggie’s evidence “that in some particular respects we did not consider to be credible”.

They also considered that other parts of her evidence were “transphobic”, though there was no legal definition of the term and they didn’t think it affected her credibility.

The main point of contention was over what happened in the changing room. The tribunal preferred Upton’s version of events, not least because he had written his version down shortly afterwards.

Peggie’s account was not recorded until several months later and the tribunal accepted her recollection may be imperfect, but they questioned inconsistencies in her account.

They felt she was looking for a confrontation, which was why she did not go into the toilet cubicle to change. They felt Peggie had badgered Upton and reduced him to tears. They went further and said that Peggie’s behaviour in tackling Upton amounted to harassment.

Wherever there was any dispute, they preferred Upton’s evidence to Peggie’s. He was clearer and more candid, they said.

The tribunal disagreed with Peggie’s evidence on where she usually changed - in the open changing room or in a closed toilet cubicle. Peggie said she didn’t usually use the toilet cubicle.

Two other members of staff said she did and the tribunal took their word for it: “We accepted their evidence, and considered that on such an issue the claimant not being accurate about it was an issue of credibility not reliability.”

One was another nurse. The other was Davidson, who didn’t regularly use the changing rooms and who had responded to Upton’s first report of the clash with Peggie by saying: “This is totally unacceptable”.

Davidson then conducted the initial investigation into what happened, an investigation so obviously flawed that it had to be abandoned and restarted with someone else in charge.

This is the same Esther Davidson who had told the tribunal she believed “we should treat people as the sex they stipulate they are”. The tribunal accepted her version of events.

The second specific issue the tribunal had with Peggie’s evidence was over remarks she’d made to Upton likening his presence in the changing room to that of a man in a women’s prison - namely Adam Graham, aka Isla Bryson, a double rapist.

Upton felt he was being likened to a rapist. Peggie argued she was just referring to Bryson’s sex and didn’t know about details of his case. The tribunal thought she should have known and didn’t believe her.

The third related to a message she’d shared with friends which referred to floods in Pakistan “in the most highly offensive terms”. Peggie had sought to pass this off as “dark humour” and trying to provoke a reaction. They didn’t believe her: “In our view it was an untruthful attempt to downplay what she had done.”

Their more general concerns was that she held views which collectively could be described as transphobic: “The view we formed from the evidence was that the claimant does not consider that a trans person is anything other than a male whatever the views of the second respondent.”

Despite this, they concluded that as transphobic wasn’t a term of law and there was other evidence to suggest she treated trans patients appropriately, it didn’t affect her credibility.

There were some other instances where they also preferred evidence from the NHS Fife side.

But they did note that other attacks on her credibility and reliability were unfounded: “the evidence was of an unblemished thirty-year career until the Christmas Eve incident, and of there being no patient complaints of any kind.”

It was on this basis that the tribunal appears to have formed its opinion on Peggie’s credibility as a witness. To put that in context it is worth taking a deeper dive into some of the evidence they heard from other witnesses they concluded were credible.

“who, out of a middle-class doctor and a working class nurse, was most credible? It was definitely the doctor, the middle-class tribunal decided”

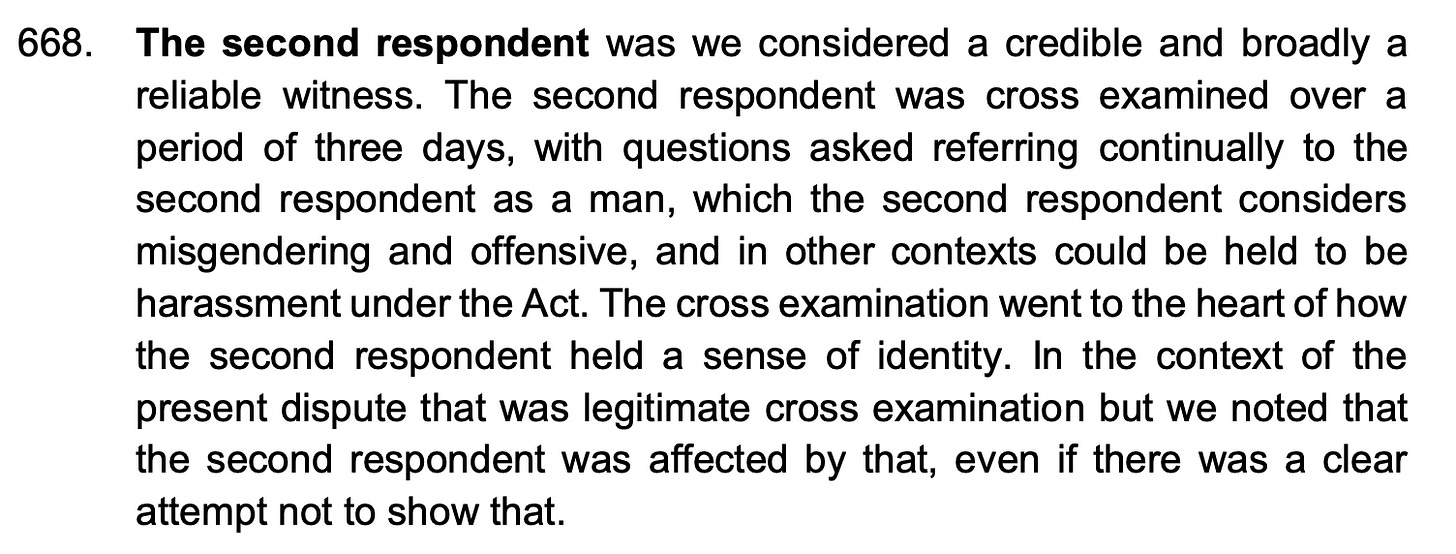

Upton was the first witness for the respondents. He told the hearing he was a woman who had the right to use the women’s changing room and that there was no agreed definition of biological sex. It was, he claimed, a “nebulous dog whistle”.

He was female and was biological, he said, so he was “biologically female”. In the judgment, the tribunal disagreed and ruled that he was a man. But they still concluded he was a “credible and broadly a reliable witness’.

Peggie’s team called an expert who showed that Upton had altered notes he’d provided as evidence of events. The tribunal accepted that they had been changed and that Upton had not recorded them contemporaneously, as he had claimed.

One note had been created two months after the incident it described. But that did not mean Upton was lying or had given perjured evidence or that it was evidence of dishonesty, they said.

“We concluded, from the evidence overall, that the second respondent had not lied to us about it, but that contrary to the second respondent’s evidence the notes were not all made contemporaneously.”

He’d probably just forgotten that he didn’t make the note when he said he did, they added. “It was inaccurate in part, but in our view honestly so,” the judgment said.

He’d also been “severely impacted” by events, they said. “It is in our view unsurprising that when giving evidence these details were not recalled accurately.”

In summary, they said, there were some areas on which they accepted Upton’s evidence and others on which they did not. But they still considered him credible and preferred his version of events to Peggie’s.

Not so the skilled witness Jim Borwick, called by the Peggie team and whose evidence the tribunal accepted proved the notes had been changed. Much of his other evidence was dismissed because they questioned his impartiality.

Borwick had made a remark based on his conclusions which they considered suggested Upton had been trying to mislead the tribunal. They thought it irresponsible and ruled that much of his evidence was therefore unreliable.

NHS Fife’s witnesses, on the other hand, were generally believed, whatever their shortcomings.

Dr Maggie Currer, a consultant, admitted she had been “factually inaccurate, and that she knew that at the time” when she said that Peggie had been reported to the Nursing & Midwifery Council. She couldn’t explain why she did it.

The tribunal recorded that Currer had made the claim in an email to a “need to know” group of NHS Fife staff. She’d said it should not be shared with anyone outwith the group. She urged them to avoid “foot-in-mouth syndrome”.

The tribunal conceded that the email contained an “admittedly inaccurate comment”. It had also been withheld despite an order from the tribunal to disclose it. Despite this, they concluded Currer was still a “credible and generally reliable” witness.

Dr Kate Searle, Upton’s supervisor, admitted in evidence that speaking to a witness despite being warned not to was a “flagrant breach” of those warnings. The tribunal found that she’d not “maintained the confidentiality of the process”.

It was Searle that Upton turned to initially to report the clash with Peggie, emailing her in the middle of the night. She declared Peggie’s actions were “completely unacceptable” and also suggested reporting it to the police.

Searle wrote to the department’s consultants describing what happened as a “hate incident” and saying she’d told Upton he had their support. The tribunal said the emails should not have been sent and breached the confidentiality of the investigation.

She accepted that “in a number of respects that messages she had sent in relation to the investigation process, and actions she had taken, were not appropriate”.

Like Borwick, the tribunal ruled that she was not impartial. She was a supporter of Upton, had called the clash with Peggie a “hate incident” and acted as a representative for Upton. Unlike Borwick, they still considered her evidence reliable.

It was Isla Bumba, NHS Fife’s equality and diversity lead officer, who advised that Upton could use a female changing room, a decision central to the case, despite not having produced a policy on trans staff.

The tribunal considered Isla Bumba a credible witness, despite Bumba having informed them that she did not know what sex she was or what her chromosomes were, but that she would guess that she was female.

“I don’t know what my own body is made of biologically. No one knows what their chromosomes are or their hormonal composition,” she said.

Bumba, the tribunal noted, “has below her email signature a logo stating ‘LGBT Ally’ and reference to the Equality Lead Network.”

There were some things she couldn’t remember or remember in detail, including a conversation about Upton’s gender identity. The tribunal preferred another staff member’s version of events. But in the same paragraph they concluded Bumba was a credible witness.

Nurse practitioner Fiona Wishart was in the changing room with Upton and Peggie on Christmas Eve: she claimed not to be able to remember what happened that night. But she was sure Peggie regularly changed in the toilets. The tribunal believed her over Peggie: she was “entirely credible”.

Nurse Lindsey Nicoll was a former friend of Peggie but they had fallen out and she had said on two occasions that she hoped Peggie would be struck off.

The tribunal concluded she disagreed with Peggie’s personal views and accepted they’d have to treat her evidence with “substantial caution in light of the adverse commentary”. But they still considered her evidence to be credible and generally reliable.

The tribunal doubtless believes that it acted fairly and was correct in its findings of fact, just as it doubtless believes it was right in law, despite the criticism it has faced from legal experts and those who question the accuracy of the quotations it cites.

And of course it is entirely possible that the panel weighed up every single bit of evidence and decided that the NHS Fife side were simply good and decent people who could not tell a lie and that Peggie was a wrong ‘un. Only they know.

I agree. The tribunal states that GC beliefs are capable of protection under the Equality Act. On the surface, this looks like compliance with Forstater. But in practice, the tribunal treats the claimant’s GC belief as something that must be tolerated only if it causes no friction, and measures her conduct against an unstated norm of affirmation, inclusion, and emotional validation of the second respondent. As a result, GC belief is accepted abstractly but problematised concretely.

The judgment frames the claimant’s discomfort as requiring justification, while the second respondent’s expectation of comfort, affirmation, and ease is treated as reasonable. The tribunal never seriously entertains the possibility that discomfort at a male-bodied person in a women’s changing space could be a deep, non-negotiable belief-based response, rather than a prejudice to be doubted, corrected or managed away. Instead, discomfort itself becomes evidence of “avoidance”, and avoidance becomes evidence of hostility. Whilst the Tribunal gives unnecessary detail of the sexual assault on the Claimant when she was 17 it is never understood how this might have added to her distress.

In paragraph 634 the tribunal shifts from describing what the claimant believes to evaluating what kind of person that belief makes her. Her reference to the second respondent “undergoing some form of process” is treated not as a factual description consistent with GC belief, but as indicative of a dismissive attitude towards gender reassignment as a protected characteristic. From there, the tribunal goes further, suggesting that her belief that a trans woman remains male is potentially transphobic. This is proof the Tribunal does not respect the Claimant’s beliefs. A belief that Forstater says must be protected is re-labelled as suspect.

The tribunal does not see that the second respondent’s note taking of the alleged incidents of the Claimant’s avoidance shows that he does not believe that it is valid to hold gender critical views. He is recording a perceived lack of eye contact as evidence of hostility and not as evidence of discomfort. He did not, when commencing employment, go to Human Resources and ensure written policy exists that he can use the changing room instead he hid behind a claim that he had used the female changing room at his previous employment without incident and a conversation with Dr. Searle but not one with HR. Having done this he ensconced himself in the changing room and the only choice for a woman objecting is to avoid or challenge. He put the pressure to establish what is policy onto a woman to complain. Thereby from the outset a woman objecting is going to feel high levels of discomfort, indecision, confusion and may make mistakes in how she progresses her distress. None of these choices by the second respondent are perceived by the Tribunal. In their view it is assumed it was entirely reasonable the second respondent occupied the changing room until challenged. His note taking was commendable.

T

he judgment operates as if gender reassignment requires affirmation and accommodation while gender critical belief requires restraint, self-monitoring, and near invisibility. It is something shameful like her alleged racism - unnecessarily allowed into the case to undermine the claimant’s credibility. If the claimant can’t show other women object the assumption is they don’t object because the norm is inclusion.

The claimant’s worldview is read through a moral lens already tilted against GC assumptions, her behaviour is interpreted in light of that moral suspicion, and her sincerity is measured against standards she could never meet without abandoning her belief. She is not just judged for what she did, but for how she sees the world.

The tribunal’s failure is not that it rejected GC beliefs outright .It is more damaging: It accepted GC belief in theory, but treated its lived expression as inherently suspect, destabilising, and in need of correction.